It started with a photograph. Black and white, developed from film, an artifact of the era it came from.

The photo itself was nothing special, most likely snapped by a dispassionate photojournalist assigned to capture another parade in Chinatown. However, it was remarkable in one way. In it, sitting next to two other dignitaries in the backseat of a convertible was Anna May Wong. Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star.

A split-second gaze at this photo as an impressionable 19 year old was enough to reel me in and bond me to Anna May Wong for life (at least it seems that way; I’m 35 now). Her mere presence—an Asian American woman, beautiful and glamorous, hair coiffed and curled, being given the VIP treatment—spoke to me in ways I’m still trying to understand.

Of course, now that I’m writing a book about her, I’ve perused hundreds of photos of AMW. Google her name and you’ll discover that, in spite of disappearing from the popular consciousness, she’s been here all along. Her cult fans on Instagram, eBay, Etsy, and assorted blogs, driven by a rabid desire to possess more of her, have kept the flame alive (and that’s no dig because I’m one of them). I’ve heard of at least one fan who still sweeps AMW’s grave in the Angelus Rosedale Cemetery and adorns it with fresh flowers.

The vast trove of images that exist of her is not by accident. Like other shrewd actresses of her day, AMW invited the fascination that came with her growing celebrity and self-fashioned her image for public consumption. Cecil Beaton, Man Ray, Edward Steichen, and Carl Van Vechten—the most famous photographers of her time—made portraits of AMW. She understood that the proliferation of her image, printed, reproduced, and distributed for the masses, contrary to her mother’s fears that it would cause her to lose her soul, actually extended her life, imprinting her spirit onto millions of people who would never lay eyes on her in the flesh. AMW lives on, in part, because of these photographs.

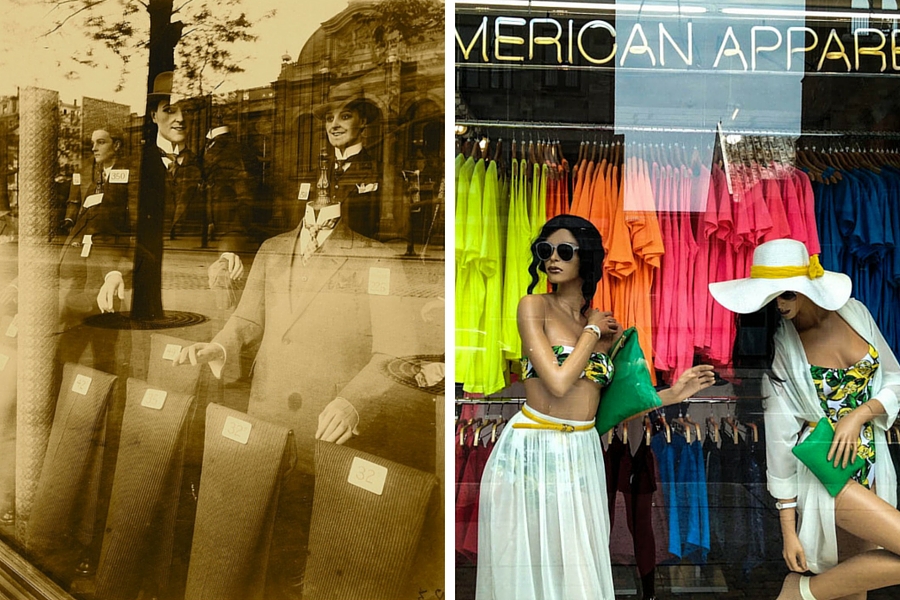

And as artifacts, they also betray the perceptions and biases of their makers. Some are impossibly modern, like Van Vechten’s portraits of AMW in a white cropped wig. Many are excessively orientalized, whether through background props, clothing, gesture, or something as simple yet evocative as a peony in full bloom.

To be sure, AMW had a hand in her own exotification. “I love American clothes,” she told a reporter at Picture Play in 1927, “but I realize that I look better if my gowns have a suggestion of China about them. And it’s good business, too!” She did so not because she saw herself as an exotic, foreign creature (who, really, would ever see themselves that way?), but because that was how she had been sold to the movie-going public. She was the Oriental beauty, the helpless China doll, and alternatively, the treacherous Dragon Lady. Her Chineseness was the feature that made her distinct and, irrevocably, defined her career as an actress in a highly racialized America.

My favorite photo of AMW is not one of these. You have to sift through the endless scroll of Google image search a bit before you get to it. Taken in the late 1920s by Paramount stills photographer Otto Dyar, AMW poses at the edge of a pool in a modest bathing suit and smiles directly at the camera.

She would have been around 25, and her youthful exuberance is unmistakable. I love this photo of AMW because in it she looks so effortlessly American, beguiling in her self-assuredness, a woman in her prime sitting poolside in the California sunshine. To me, this is who she really was. Not the China doll.

This is important. Why? The U.S. has a long history of casting Asian Americans as the perpetual foreigner. AMW was born in Los Angeles in 1905. Her parents, too, were born in Northern California. Being Chinese American wasn’t a thing in the 1920s and 30s when her career blossomed, not because Chinese Americans didn’t exist, but because the concept itself was unfathomable.

“Anna May Wong, among Americans, is so thoroughly one of us that her Oriental background drops completely away,” a surprised reporter recounted for the pages of Pictures and Picturegoer magazine. “Does she, chameleon like, become thoroughly Chinese when among her own people? Are her Americanisms merely part of a clever pose?”

In fact, before the country would acknowledge the presence of “Asian Americans” (a term that was coined by activists in the 1960s), it had to grapple with its distrust of European immigrants. President Woodrow Wilson gave credence to the phrase “America first” in a speech to the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1915. He expounded on the necessity of “calling upon every man to declare himself, where he stands. Is it America first or is it not?” The sentiment was shared by many. Under Woodrow’s presidency and for decades to come, the phrase hyphenated American—Italian-American, Irish-American, German-American, etc.—was a dirty word.

You don’t have to look far to see how this kind of thinking has shaped the America we live in today, more than a hundred years later. The man in the White House (for the next 17 days, anyway) casually and consistently uses slurs like “kung flu” and “China virus” to lay blame elsewhere for the COVID-19 pandemic, inciting verbal abuse and violence towards Asian Americans.

For her part, AMW introduced the American public to the reality of her existence—as a Chinese American, as an Asian American, and as an independent woman with a career. Her natural magnetism, transmitted through the magic of film, made it hard to look away.

There are other iterations of AMW posing next to the pool from her portrait session with Dyar, nearly all of them equally enchanting. Still, I like this one best. A reproduction of it sits on my desk as I write this, reminding me what it looks like to be American.

In 2020 I began working on a book about Anna May Wong for Dutton Books. This short essay first appeared in Half-Caste Woman, a monthly newsletter that allows me to ruminate on some of the discoveries I’m making and offers a chance for subscribers to glimpse the messy process that is writing a book. I send new dispatches on the first Sunday of every month about Anna May Wong and topics related to race in America, representation in Hollywood, or just to share the fun little gems I come across. Subscribe here.

![“A lot of my friends who voted for [Trump] say give him a chance. Well, I’m trying. Try! I want him to try. Just give us some frickin’ effort.” —Anne MacDonald, Greenville, Ohio](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/536c3b94e4b0ad24d25d55f8/1492991167856-XK18SIHN6NYPUDNC0S53/womens-march-4977.jpg)