William & Park| Passion before faith: an artist finds her truth

Embarking on a life devoted to art is a terrifyingly delicate thing, but one that is strengthened and renewed daily by the underlying force propelling it: the need to create. For Sara Erenthal, the need has always been there, yet it took years of drawing on the walls and doodling before she realized what she was doing was ‘art.’

In fact, when Sara speaks of her previous life, she remarks that it’s like talking about a complete stranger, so sharp is the disconnect. At age 17 she fled the confines of her religious upbringing—her parents belonged to an ultra-Orthodox sect of Judaism—in order to escape an arranged marriage. Whether she knew it or not at the time, that definitive break with tradition set her on a trajectory towards the life of an artist.

Two years spent traveling through South East Asia and India proved formative. It was in India that making art became cemented into her daily routine. “People started seeing [my art] more. One guy asked to buy something, so that threw me off. Then I had this realization that I really have to pursue this, and that’s all I cared about. It didn’t matter to me if I had money or not, I just needed to make art.

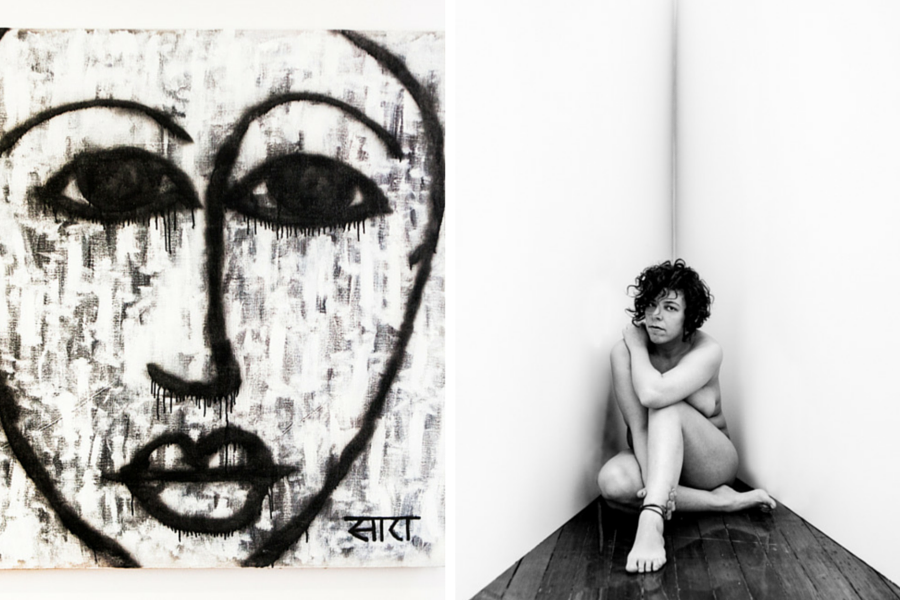

They say necessity is the mother of all invention. As an artist, Sara is completely self-taught. Her work has a practical, use-what-you-got bent to it and spans across mediums—coffee splattered on notebook pages, paint on a cheap whiskey bottle, a windowpane tossed out on the sidewalk, along with many paintings on canvas or what she terms ‘subconscious self-portraits.’

Miraculously, Sara has found a way to sustain an existence dedicated to art in a high-stakes city like New York without deferring to a day job. She’s survived the last three years by bartering housework and errands in exchange for shelter, and she buys food and art supplies with the money she makes from selling her art. But spartan ways also necessitate the daily calculus of deciding whether to buy a sandwich at the bodega or pay for the $2.50 train fare home.

There’s no reward without struggle, and for Sara, leaving behind her religion and a material existence has only opened up the possibilities for her true passion.

“I gave up on a lot of those luxurious things that people need in life. If I want to be free and be able to make art whenever I feel inspired, I don’t want to have any other distractions or schedules. I’m not just aimless, I’m not just roaming around without a goal. I’m actually working towards doing something better, becoming better at what I do. That’s what keeps my crazy life in check.”

Where do you draw your inspiration from?

A lot of my work is subconscious self-portraits or portraits of other people who affect me. So even if they’re not so literal, it’s a lot about interactions and how I feel about them. The first modern art I was exposed to was African art by a friend who was making these wood-carved sculptures. That was an image that got stuck in my head without realizing it.

Sometimes I find out about other artists’ work and I think, oh, that actually reminds me of myself. And I get a little feeling of confirmation. If that artist made it, then I can too. I make sense now because she did that. If people can appreciate that, then maybe I’m doing something good.

What was the first major piece of art you sold?

It was a fabric collage and portrait. A wonderful woman named Maggie bought it; she’s a Haitian art collector. She has a wonderful collection of over 100 original, beautiful pieces. She likes to support emerging artists. She bought my first piece which was actually made in her house and inspired by the work that she had in her house. It was a piece about her and she bought it.

Since you’ve started actively thinking of yourself as an artist, how has your work changed and developed?

It’s gotten better because I’ve done it more. Practice makes perfect. The more time we spend on anything we tend to get better at it. It’s funny, when I look back now, I used to think the work I did three years ago was good. But I feel like that whenever I’m doing something new. I’m sure in ten years I’m going to look back at the work I’m doing now and I’m gonna laugh.

Do you have a favorite medium?

I don’t think I’ll ever stop exploring mediums. The possibilities are endless in what I can make and things I’d like to play with. Obviously, the more of a stable studio situation I would have, the more intricate stuff I’ll probably make because I’ll have more of a chance to store things that I find and [be able to] work on bigger things.

Do you have a routine or way of getting into the right frame of mind when you’re working on a piece?

Most of my work is extremely impulsive. I can finish things in two days, sometimes even a few hours, depends what I’m working on. Because it’s a mood, so I have to be in that same mood when I start it until I finish it. When I feel a certain way, that’s when I work, I’m going to do this right now. I say I want a studio, but really I want a studio that has a bed in it. There are days when I don’t leave the bed but I bring the art supplies to the bed and I work in bed.

For you, art is really a way to capture emotions and express something that you’re feeling.

I don’t even plan that emotion, it just comes through. Once I start working I kind of lose control of what my hands do, it just takes over. I don’t even realize sometimes why I’m doing something a certain way until a piece is done. And I look at it, and I’m like, oh, that makes sense. I just finished this piece two days ago. It’s a self-portrait. I started the piece and I didn’t do the face, and I kept thinking, I don’t want to do it right now, I just don’t want to do the face. And as it came together, I realized this is not supposed to have a face. It wasn’t planned, it just happened.

You have a very unique signature. What’s the story behind it?

It’s Sara written in Sanskrit because India really changed my life and it’s where I started drawing the most. I started using my signature in Sanskrit when I was making clothes. All the clothes were handmade and unique pieces, like pieces of art, and I wanted to create some kind of label for a tag. So I came up with this design with my fingerprint in paint and then my name in Sanskrit. It was supposed to be just for that, but I continued using it.

At first I thought it was silly, why am I signing my name in Sanskrit, I’m not Indian. What’s really funny, though, is then people came up to me and said, do you realize it looks like it says “art” on it? I didn’t even realize that. And then there was something even deeper [laughs], even deeper! I have a Yiddish name, and my Yiddish name is Hindel, but I was called Hindy as a kid. I can’t stop using this signature because there are too many layers of meaning.